Our manuscript is published at International Workshop on Graphs in Biomedical Image Analysis, MICCAI 2022 https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-21083-9_12

In neuroimaging research, sharing open datasets boosts transparency, reproducibility, and cross-disciplinary work, advancing our understanding of brain functions. Yet, the diversity in brain atlas standards complicates data sharing and connectome comparability. Innovative domain adaptation techniques, like entropic Gromov-Wasserstein distance and optimal transport with matrix factorization, help overcome these challenges by enabling the mapping of connectomes across different atlas spaces. This improves machine learning’s predictive accuracy using varied datasets and is essential for maximizing the potential of open neuroimaging datasets in clinical and cognitive studies, despite data management and regulatory challenges.

Brain atlas in neuorimaging analysis

Brain parcellation facilitates both theoretical understanding and practical applications in neuroscience research by simplifying complex brain data into comprehensible and analyzable formats. Despite their utility, the field of clinical and cognitive neuroimaging research lacks a universally accepted standard atlas, with each parcellation method uniquely emphasizing certain brain features, suggesting that a universally applicable standard may not be feasible. This makes connectomes from different atlases essentially incomparable. Such heterogeneity complicates the sharing of connectomes and affects the comparability of machine learning models trained on them.

Brain parcellation facilitates both theoretical understanding and practical applications in neuroscience research by simplifying complex brain data into comprehensible and analyzable formats. Despite their utility, the field of clinical and cognitive neuroimaging research lacks a universally accepted standard atlas, with each parcellation method uniquely emphasizing certain brain features, suggesting that a universally applicable standard may not be feasible. This makes connectomes from different atlases essentially incomparable. Such heterogeneity complicates the sharing of connectomes and affects the comparability of machine learning models trained on them.

Method

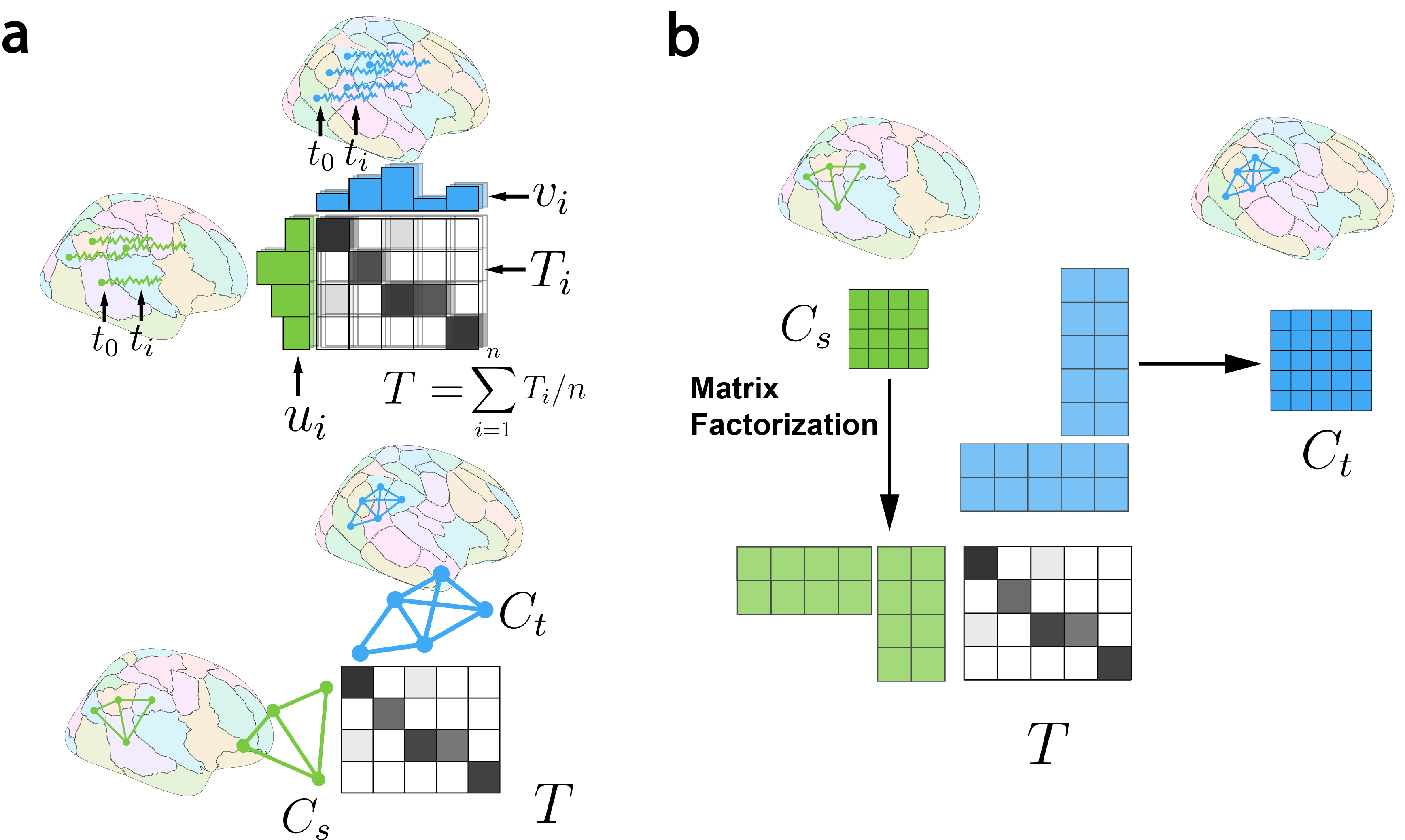

Figure 1. Flowchart of our method. a, Learning mapping between atlases with optimal transport. Node-wise timeseries data yields transportation matrices at each timepoint, with the average providing the final mapping. When only connectomes are available, node mapping is learned through graph matching. b, Decomposing the source atlas connectome into node factors, transported to the target space using the mapping learned in a for estimating target connectomes.

Figure 1. Flowchart of our method. a, Learning mapping between atlases with optimal transport. Node-wise timeseries data yields transportation matrices at each timepoint, with the average providing the final mapping. When only connectomes are available, node mapping is learned through graph matching. b, Decomposing the source atlas connectome into node factors, transported to the target space using the mapping learned in a for estimating target connectomes.

Optimal transport of node timeseries

Given the corresponding node information \(\textbf{U} = [u_1^T, …, u_d^T] \in \mathbb{R}^{n_s\times d} \) of parcellation \( \alpha \) and \(\textbf{V} = [v_1^T, …, v_d^T] \in \mathbb{R}^{n_t\times d}\) of parcellation as \(\beta\), the optimal transport \(\textbf{T}\) is learned by solving the following equation: $$ \min_T \sum_i C(v_i,\textbf{T}(u_i)):\textbf{T}_{\sharp \textbf{U}} = \textbf{V} $$

Graph-matching using gromov-wasserstein discrepancy

Gromov-Wasserstein Discrepancy compares graphs in a relational way, measuring how the edges in a graph compare to those in the other graph. It is a natural extension of the Gromov-Wasserstein distance defined for metric-measure spaces. In graph matching, a metric-measure space corresponds to the pair \((\textbf{D},\textbf{u})\) of a graph \(G(\mathcal{V},\mathcal{E})\), where \(\textbf{D} = [d_{ij}] \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times n} \) represents a distance matrix derived from edge set \(\mathcal{E}\), \(\textbf{u} \in \Sigma^{n} \) is a Borel probability measure defined on node set \(\mathcal{V}\). In our case, the distance matrix is calculated using \(d_{ij} = 1/(1+c_{ij})\) from structural connectome \(\textbf{C}\) and \(\textbf{u}\) is calculated based on the normalized degree of graph. Given two graphs \(G(\mathcal{V}_s,\mathcal{E}_s)\) and \(G(\mathcal{V}_t,\mathcal{E}_t)\), the Gromov-Wasserstein discrepancy between \((\textbf{D}_s,\textbf{u}_s)\) and \((\textbf{D}_t,\textbf{u}_t)\) is defined as

$$ d_{GW} := \min_{\textbf{T}} \sum_{i,j,i’,j’} L(d^s_{ij},d^t_{i’j’})T_{ii’}T_{jj’} $$

Dataset

This study used data from three datasets: the UK Biobank, the Human Connectome Project (HCP), the Human Connectome Project in Development (HCPD), the Yale Low-Resolution Controls Dataset (Yale).

Results

Transformed connectomes are similar to target connectomes

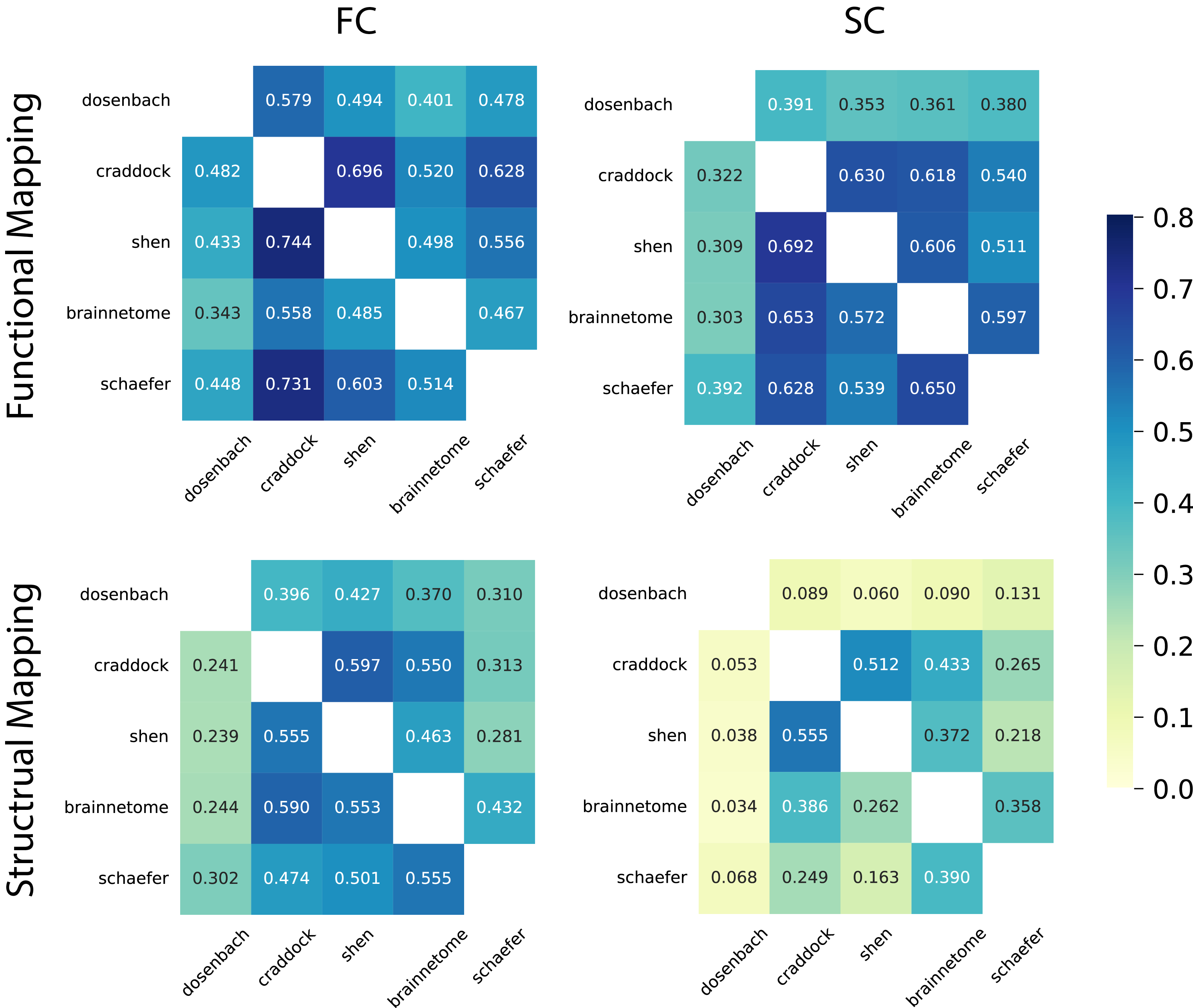

Figure 2. Correlations between transformed connectomes and their respective target connectomes. Each row corresponds to a source atlas, and each column corresponds to a target atlas. Data transformation was conducted using functional mapping learned from fMRI timeseries in the Yale dataset, as well as structural mapping derived from the structural connectomes in the HCP dataset. Validation was performed on functional connectomes sourced from the HCP dataset and structural connectomes from the HCP development dataset.

Figure 2. Correlations between transformed connectomes and their respective target connectomes. Each row corresponds to a source atlas, and each column corresponds to a target atlas. Data transformation was conducted using functional mapping learned from fMRI timeseries in the Yale dataset, as well as structural mapping derived from the structural connectomes in the HCP dataset. Validation was performed on functional connectomes sourced from the HCP dataset and structural connectomes from the HCP development dataset.

Our analysis demonstrates the successful estimation of functional connectomes r = 0.533 and structural connectomes r = 0.502 using functional mapping. Notably, the accuracy of structural mapping appears to be relatively lower, particularly when working with connectomes transformed from or to the Dosenbach atlas. This discrepancy can be attributed to the origins of the Dosenbach atlas, which was constructed primarily based on the analysis of task activations and exhibits a lesser degree of similarity to other atlases. In contrast, we observed significantly higher correlations when transforming data from the Shen atlas to the Craddock atlas (r = 0.744 for functional connectomes and r = 0.692 for structural connectomes). Both the Shen and Craddock atlases rely on the clustering of time series data using variations of the N-cut algorithm. These observed correlations serve as an indicator of the degree of similarity or overlap between the atlases.

Models trained on the transformed connectomes retained essential predictive information

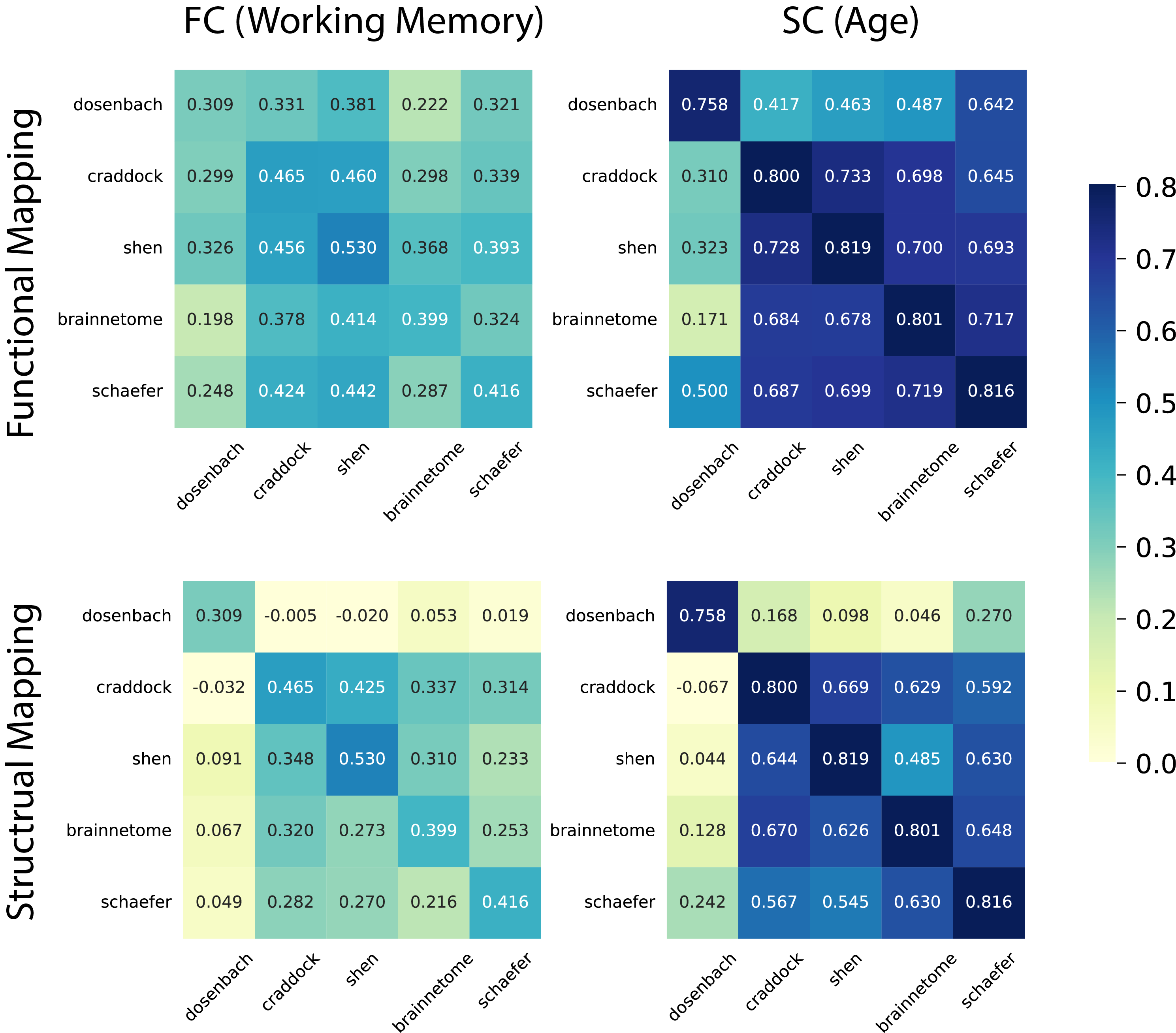

Figure 3. Predictive performance (correlation) of models trained on transformed connectomes and tested on target connectomes. The diagonal presents the performance of the models trained on target connectomes. We used functional connectomes to predict working memory scores and structural connectomes to predict age.

Figure 3. Predictive performance (correlation) of models trained on transformed connectomes and tested on target connectomes. The diagonal presents the performance of the models trained on target connectomes. We used functional connectomes to predict working memory scores and structural connectomes to predict age.

Regression models using transformed connectomes predicted phenotypic measures for the target connectome. Although slightly less accurate than ground truth models trained directly on target connectomes, they maintained high accuracy, especially when the Dosenbach atlas was excluded. These predictive model results aligned with estimation accuracy findings, highlighting the superiority of functional mapping over structural mapping. However, in cases where only paired structural connectomes of two atlases are accessible, structural mapping can serve as a substitute for functional mapping.