Data heterogeneity, notably due to variations in brain atlases, poses a significant challenge in federated learning (FL) and meta-learning within neuroimaging, especially in functional MRI (fMRI) studies of neurological diseases. The diversity of brain atlases leads to inconsistencies in data representation, complicating the aggregation of insights across different datasets in a federated learning framework. This heterogeneity affects the collaborative training of models, as it introduces variability in data distributions and model architectures across institutions. Similarly, in meta-learning, the goal of quickly adapting models to new tasks is hindered by the disparate data spaces generated by the use of various atlases, requiring more sophisticated approaches to achieve effective generalization. Addressing the challenges posed by atlas heterogeneity is crucial for the successful application of FL and meta-learning in neuroimaging, aiming to enhance precision medicine and the accuracy of fMRI analysis.

Method

Overcoming atlas space heterogeneity in federated learning for multi-site connectome modeling

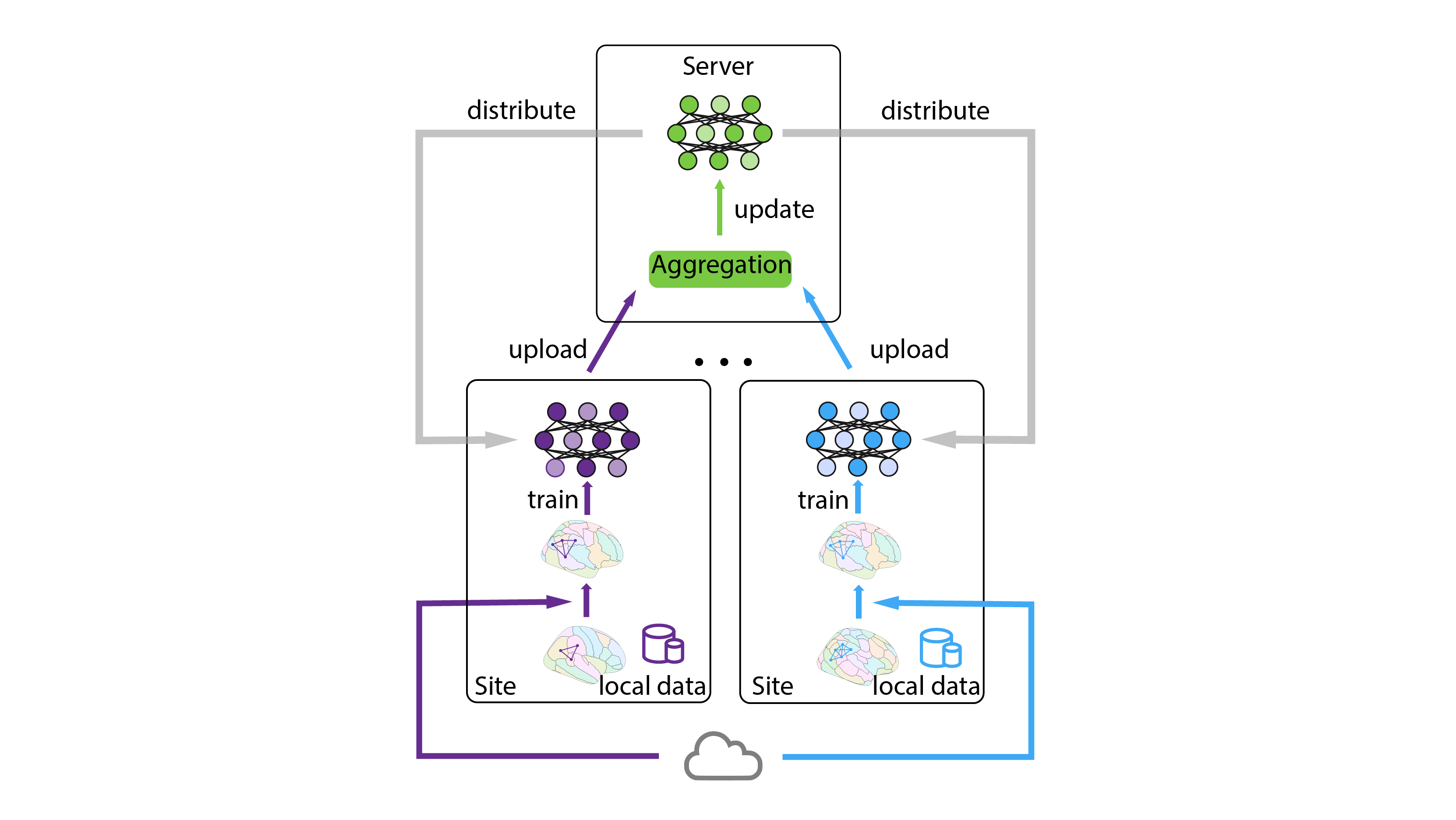

Figure 1. Federated learning framework for sites with connectomes from different atlases. Initially, connectomes are locally transformed into the target atlas using online mapping resources. The local models, trained on the transformed data, are subsequently aggregated on the server and distributed back to the local nodes for updates.

Figure 1. Federated learning framework for sites with connectomes from different atlases. Initially, connectomes are locally transformed into the target atlas using online mapping resources. The local models, trained on the transformed data, are subsequently aggregated on the server and distributed back to the local nodes for updates.

Meta Learning across heterogeneous atlases space

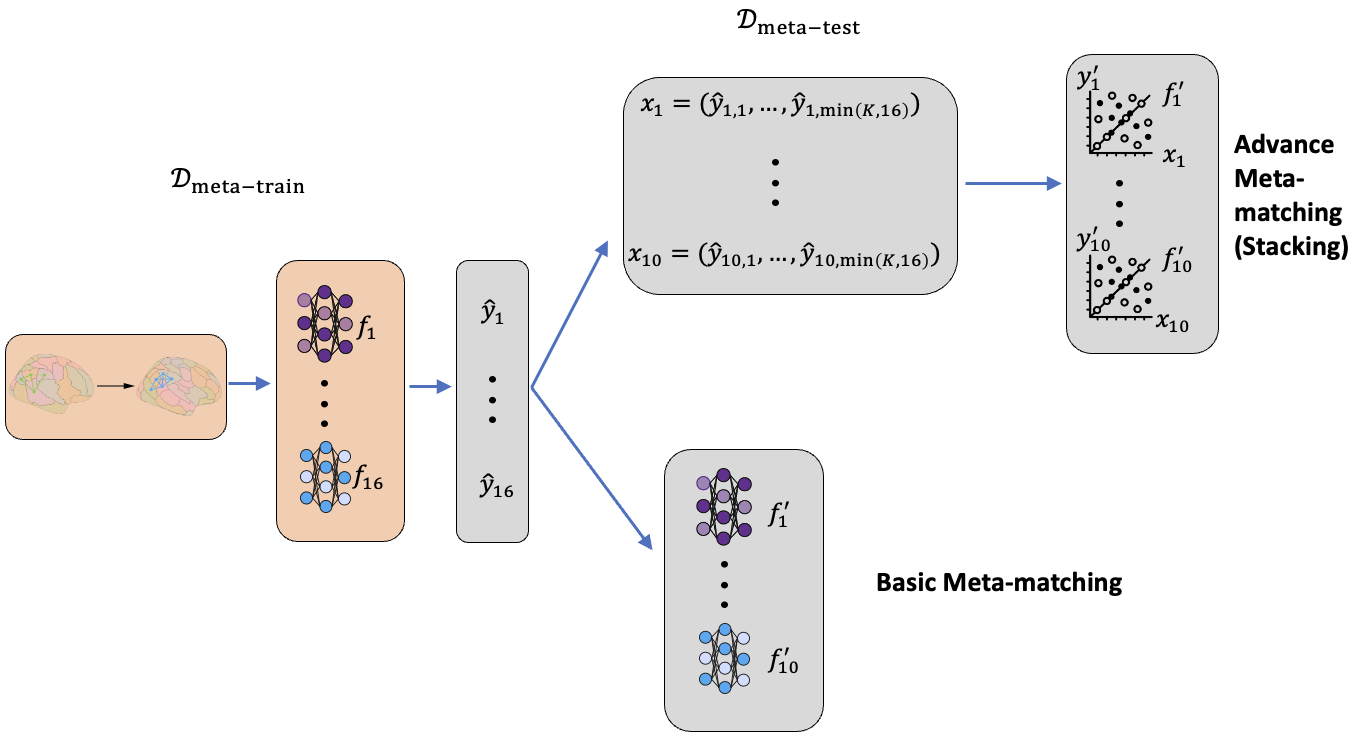

Figure 2. Meta learning framework for connectomes across atlases

Figure 2. Meta learning framework for connectomes across atlases

Meta-learning, fundamentally regarded as “learning to learn,” is an advanced concept in machine learning that centers around crafting a meta-algorithm, denoted as \(\mathcal{M}\), which enhances its learning efficiency by harnessing experience from a diversity of tasks. In the meta-training stage, \(\mathcal{M}\) is trained on a set \( \cal T_{train} \), with each task \(T_i \in \cal T_{train}\) having its dataset \(D_i\). This stage aims to optimize \(\mathcal{M}\) such that it acquires a generalized learning strategy, capable of rapid adaptation to new tasks. This involves a dual-layered learning process: a task-specific learning for each \(T_i\) , where a model \(f_{\theta_i}\) is learned using \(D_i\), and a meta-level learning where the parameters of \(\mathcal{M}\) are adjusted based on the performance across these varied tasks. The objective is to enable \(\mathcal{M}\) to provide effective initial settings or learning approaches for unfamiliar tasks.

Following this, the meta-testing phase evaluates \(\mathcal{M}\) using a different set of tasks, \(\cal T_{test}\), with each \(T_{new} \in \cal T_{test}\) presenting a novel dataset \(D_{new}\). The meta-algorithm is then adapted to each \(T_{new}\) using a small portion of \(D_{new}\), emphasizing rapid and efficient adaptation. The success of \(\mathcal{M}\) in meta-testing is gauged by its quick learning capability, minimal data requirement for adaptation, and high generalization performance on unseen data from \(D_{new}\).

In our setting, the data in the meta-train set and meta-test set is in different atlas space. We first transformed the data in the meta-train set to the target atlas. A Deep Neural Network (DNN) is built trained to for each task in the meta-train set. On the support set of meta-test set, we either choose the DNN that has the highest predictive accuracy on the new task (Basic meta-matching) or train a regression model using the prediction of the every DNN (Advanced Meta-matching (Stacking)). The models are then applied on the query set for validation.

Result

Federated learning with connectomes of multiple atlases improved predictive performance

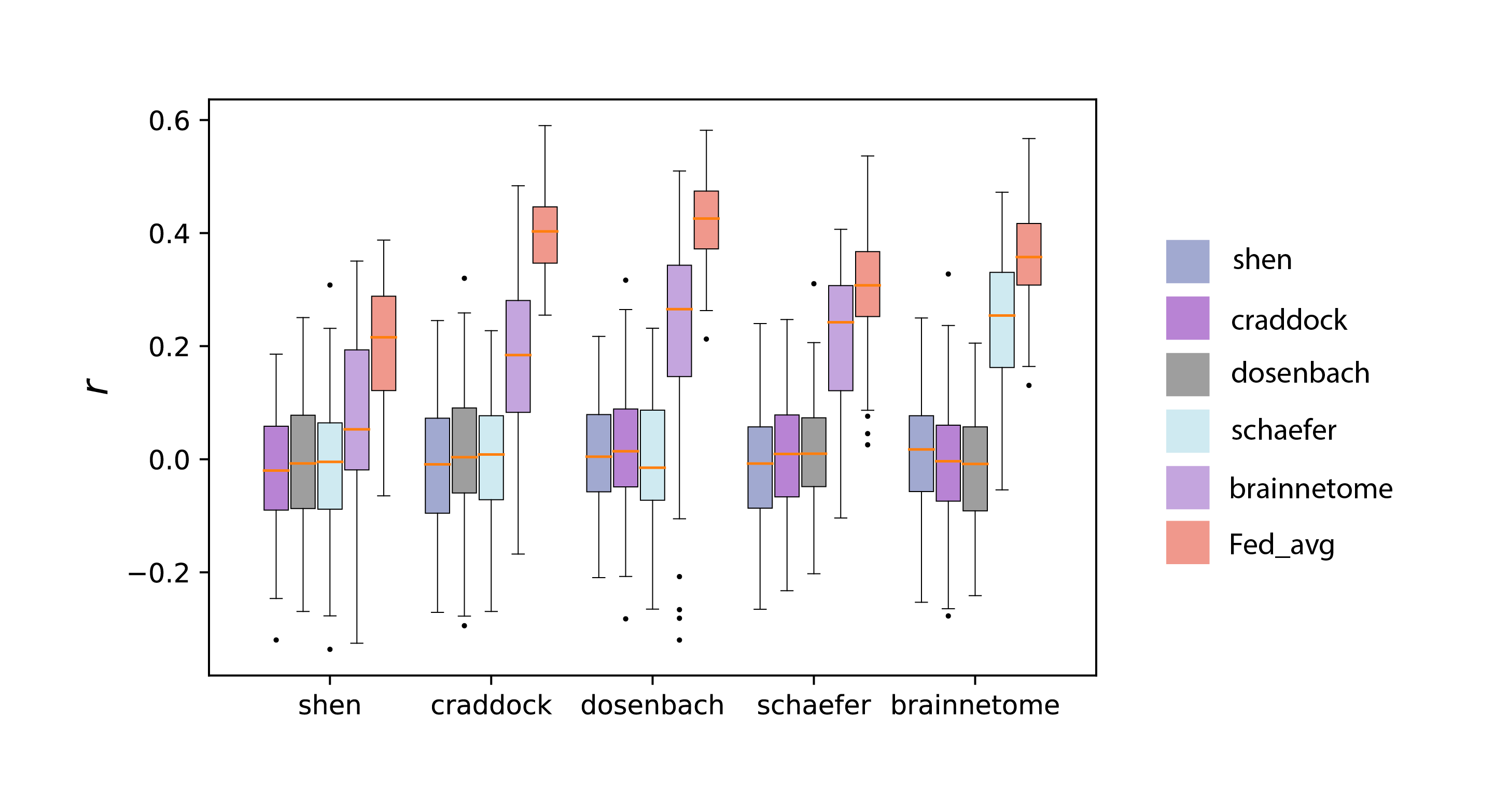

Figure 3. Predictive performance of the federated learning model (Fed_avg) and models trained independently on each site, with colors corresponding to the atlas used at the training site. The horizontal axis displays the atlas names associated with the testing sites. All the participants were split into 5 partitions (sites) for 100 times in the experiments. Stars above the boxplots of Fed_avg indicate a significantly higher prediction performance relative to all the other models (p < 0.001).

Figure 3. Predictive performance of the federated learning model (Fed_avg) and models trained independently on each site, with colors corresponding to the atlas used at the training site. The horizontal axis displays the atlas names associated with the testing sites. All the participants were split into 5 partitions (sites) for 100 times in the experiments. Stars above the boxplots of Fed_avg indicate a significantly higher prediction performance relative to all the other models (p < 0.001).

As depicted in Figure 3, federated learning models exhibited superior performance compared to models trained on individual sites, encompassing a range of target atlases. These single-site models typically did not achieve significant predictive results, showing the tendency to overfit seen in models trained on single sites. Additionally, Fed_avg showed increased robustness, in stark contrast to the notably higher variance of the second-best single-site models.

Meta-learning on large-scale datasets with a different atlas improves predictive performance

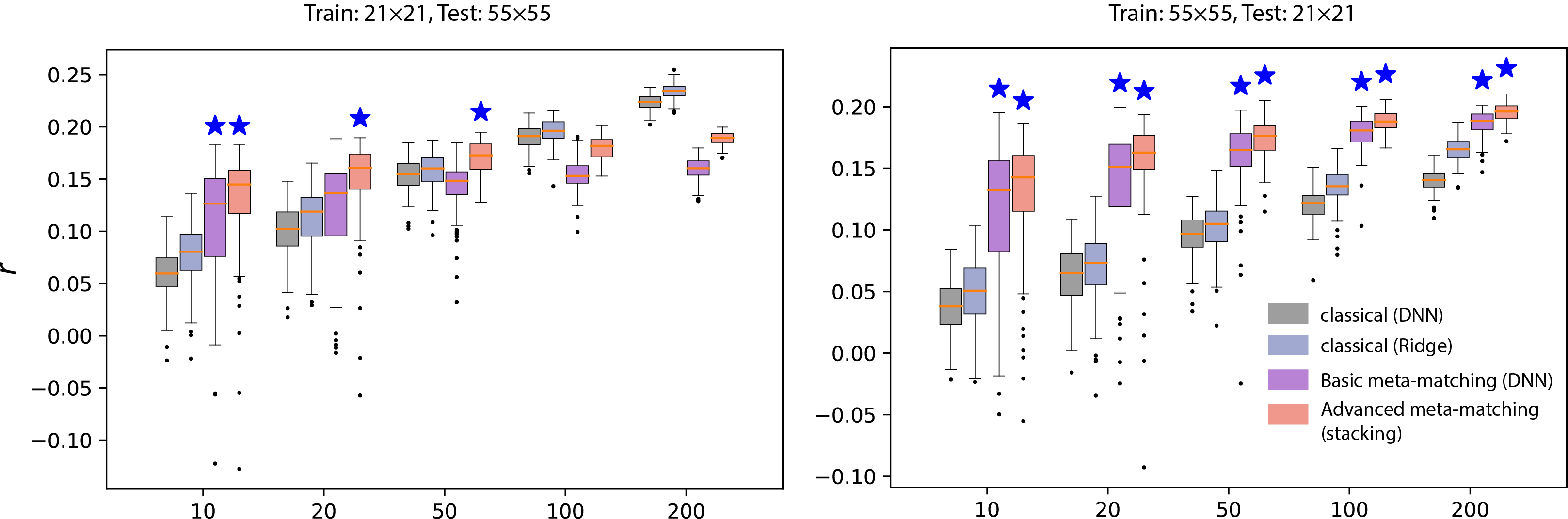

Figure 4. Meta-matching outperforms predictions from classical machine learning methods across hetergenous domain. The left plot illustrates a scenario where the training meta-set included FCs derived from 21 independent components, while the testing set FCs were based on 55 components. Conversely, the right plot displays the reversed condition, with 55 components in the training set and 21 in the testing set.

Figure 4. Meta-matching outperforms predictions from classical machine learning methods across hetergenous domain. The left plot illustrates a scenario where the training meta-set included FCs derived from 21 independent components, while the testing set FCs were based on 55 components. Conversely, the right plot displays the reversed condition, with 55 components in the training set and 21 in the testing set.

Our connectome transformation approach overcomes a limitation in the original meta-matching framework, which required connectomes in large-scale datasets to match the atlas of smaller studies. As shown in Figure 4, advanced meta-matching consistently surpasses classical methods in predictive performance across various machine learning algorithms, particularly when K is less than 50. For K greater than 50, meta-matching’s effectiveness diminishes compared to classical methods when training meta-set connectomes are transformed from low to high resolution. Nevertheless, meta-matching maintains its superiority for larger K values when the transformation is from high to low resolution. The advanced meta-matching method demonstrates the greatest stability and accuracy in predictions.